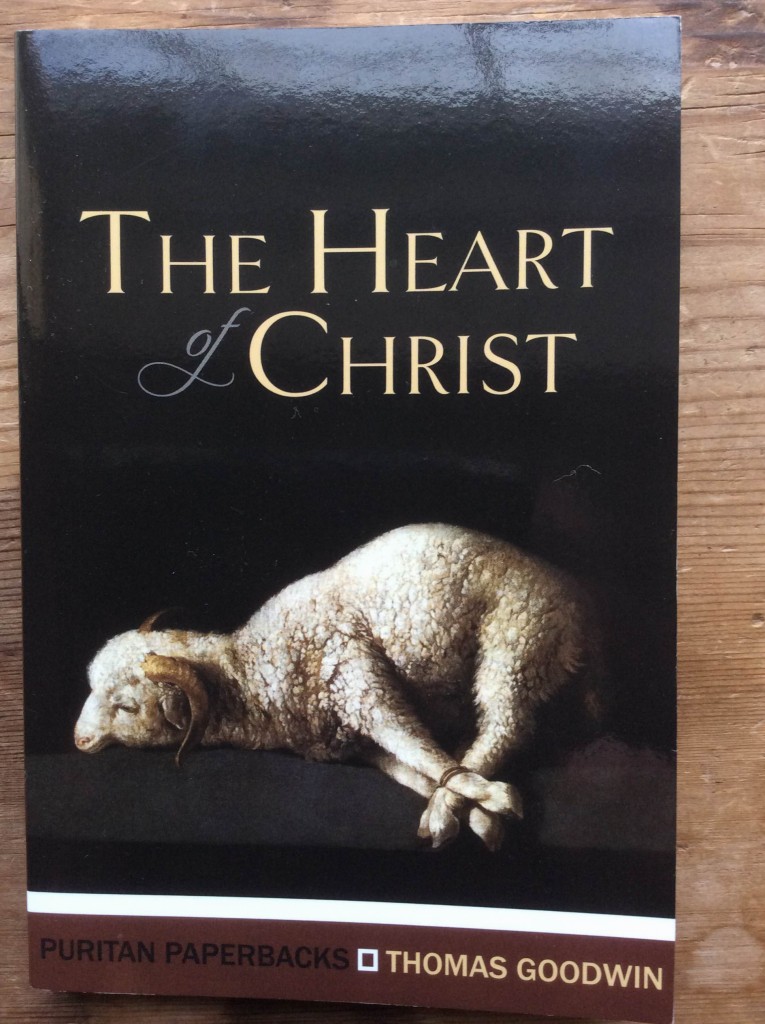

The other day I was given a copy of Thomas Goodwin’s book The Heart of Christ, from the Puritan Paperback series from Banner of Truth.

The other day I was given a copy of Thomas Goodwin’s book The Heart of Christ, from the Puritan Paperback series from Banner of Truth.

The foreword by Michael Reeves was so moving I wanted to share it. The full title is: The Heart of Christ in Heaven Towards Sinners on Earth.

How can Thomas Goodwin be so forgotten? Once ranked as a theologian alongside Augustine and Athanasius, even hailed as ‘the greatest pulpit exegete of Paul that has ever lived’, he should be a household name. His writings, while not easy, always pay back the reader, for in Goodwin a simply awesome theological intellect was wielded by the tender heart of a pastor.

As it is, Goodwin needs a little re-introduction. He was born in 1600 in the small village of Rollesby in Norfolk. His parents were God-fearing, and at the time the Norfolk Broads were well-soaked in Puritanism, so unsurprisingly he grew up somewhat religious. That all wore off, though, when he went up to Cambridge as a student. There he divided his time between ‘making merry’ and setting out to become a celebrity preacher. He wanted, he later said, to be known as one of ‘the great wits’ of the pulpit, for his ‘master-lust’ was the love of applause.

Then in 1620 – having just been appointed a fellow of Katharine Hall – he heard a funeral sermon that actually moved him, making him deeply concerned for his spiritual state. It started seven grim years of moody introspection as he grubbed around inside himself for signs of grace. Only when he was told to look outwards – not to trust to anything in himself, but to rest on Christ alone – only then was he free. ‘I am come to this pass now,’ he said, ‘that signs will do me no good alone; I have trusted too much to habitual grace for assurance of justification; I tell you Christ is worth all.’

Soon afterwards he took over from Richard Sibbes’ preaching at Holy Trinity Church. It was an appropriate transition, for while in his navel-gazing days his preaching had been mostly about battering consciences, his appreciation of Christ’s free grace now made him a Christ-centred preacher like Sibbes. Sibbes once told him ‘Young man, if ever you would do good, you must preach the gospel and the free grace of God in Christ Jesus’ – and that is just what Goodwin now did. And, like Sibbes, he became an affable preacher. He wouldn’t use his intellectual abilities to patronise his listeners, but to help them. Still today, reading his sermons, it is as if he takes you by the shoulder and walks with you like a brother.

All the while, Archbishop Laud was pressing clergy towards his own ‘high church’ practices. By 1634, Goodwin had had enough: he resigned his post and left Cambridge to become a Separatist preacher. By the end of the decade he was with other nonconformist exiles in Holland. Then, in 1641, Parliament invited all such nonconformists to return, and soon Goodwin was leading the ‘dissenting brethren’ at the Westminster Assembly. ‘Dissenting’, ‘Separatist’: it would be easy to see Goodwin as prickly and quarrelsome. In actual fact, though, while he was definite in his views on the church, he was quite extraordinarily charitable to those he disagreed with, and managed to command widespread respect across the theological spectrum of the church. Almost uniquely, in an age of constant and often bitter debate, nobody seems to have spoken ill of Goodwin.

If there was a contemporary Goodwin overlapped with more than any other, it was John Owen. In the Puritan heyday of the 1650s, when Owen was Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, Goodwin was President of Magdalen College. For years they shared a Sunday afternoon pulpit, both were chaplains to Cromwell, together they would co-author the Savoy Declaration. And both had their own sartorial whimsies: Owen was known for his dandy day-wear, his snake-bands and fancy boots; Goodwin, it was giggled, had such a fondness for nightcaps that he is said to have worn whole collections on his head at once.

First and foremost, Goodwin was a pastor at heart. Students at Magdalen College soon found that, should they bump into Goodwin or his nightcaps, they could expect to be asked when they were converted or how they stood with the Lord. And when Charles II returned in 1660 and Goodwin was deprived of his post, it was to pastor a church in London that he went.

The last twenty years of his life he spent pastoring, writing treatises and studying in London (the study sadly interrupted in 1666 when the Great Fire burned more than half of his voluminous library). Then, at eighty years old, he was gripped by a fatal fever. With his dying words he captured what had always been his chief concerns: ‘I am going’, he said,

‘to the three Persons, with whom I have had communion… My bow abides in strength. Is Christ divided? No, I have the whole of his righteousness; I am found in him, not having my own righteousness, which is of the law, but the righteousness which is of God, which is by faith of Jesus Christ, who loved me, and gave himself for me. Christ cannot love me better than he doth. I think I cannot love Christ better than I do; I am swallowed up in God… Now I shall be ever with the Lord’.

The Heart of Christ in Heaven Towards Sinners on Earth was, almost immediately, Goodwin’s most popular work. It is also exemplary of his overall Christ-centredness and his mix of theological rigour and pastoral concern. Published in 1651 alongside Christ Set Forth, the two were written for reasons dear to Goodwin: that is, he felt that many Christians (like himself once) ‘have been too much carried away with the rudiments of Christ in their own hearts, and not after Christ himself’. Indeed, he wrote, ‘the minds of many are so wholly taken up with their own hearts, that (as the Psalmist says of God) Christ “is scarce in all their thoughts.”’ Goodwin wanted us ‘first to look wholly out of our selves unto Christ’, and believed that the reason we don’t is, quite simply, because of the ‘barrenness’ of our knowledge of him. Thus Goodwin would set forth Christ to draw our gaze to him.

Of the two pieces, Christ Set Forth and The Heart of Christ in Heaven, the latter was the cream, he believed, for through it he would present to the church the heart of her great Husband, thus wooing her afresh. His specific aim in this essay is to show through Scripture that in all his heavenly majesty, Christ is not now aloof from believers and unconcerned, but has the strongest affections for them. And knowing this, he said, may

‘hearten and encourage believers to come more boldly unto the throne of grace, unto such a Saviour and High Priest, when they shall know how sweetly and tenderly his heart, though he is now in his glory, is inclined towards them’.

Goodwin starts with Christ on earth and the beautiful assurances he gave his disciples. In John 13, for example, knowing that he was shortly to return to his Father, Jesus washed his disciples’ feet as a token of how he would always be towards them; he told them of how he would go like a loving bridegroom to prepare a place for his bride; after the resurrection, the first thing he calls them is ‘my brothers’; and the last thing they see as he ascends to heaven is his hands raised in blessing.

It is as if he had said, The truth is, I cannot live without you, I shall never be quiet till I have you where I am, that so we may never part again; that is the reason of it. Heaven shall not hold me, nor my Father’s company, if I have not you with me, my heart is so set upon you; and if I have any glory, you shall have part of it… Poor sinners, who are full of the thoughts of their own sins, know not how they shall be able at the latter day to look Christ in the face when they shall first meet with him. But they may relieve their spirits against their care and fear, by Christ’s carriage now towards his disciples, who had so sinned against him. Be not afraid, ‘your sins will he remember no more.’ … And doth he talk thus lovingly of us? Whose heart would not this overcome?

It is moving stuff, and it is strong stuff. In fact, Goodwin presents the kindness and compassion of Christ so strikingly that, when reading him, I find myself continually asking ‘Is Goodwin serious? Can this really be true?’ He argues, for example, that in Christ’s resurrection appearances, because he had dealt with the sin of his disciples on the cross, ‘No sin of theirs troubled him but their unbelief.’ And yet Goodwin is so carefully scriptural that one is forced to conclude that Christ really is more tender and loving than we would otherwise dare to imagine.

Then Goodwin takes us to the heart of his argument: his exposition of Hebrews 4:15, which

‘doth, as it were, take our hands, and lay them upon Christ’s breast, and let us feel how his heart beats and his bowels yearn towards us, even now he is in glory – the very scope of these words being manifestly to encourage believers against all that may discourage them, from the consideration of Christ’s heart towards them now in heaven’.

Goodwin shows that in all his glorious holiness in heaven, Christ is not sour towards his people; if anything, his capacious heart beats more strongly than ever with tender love for them. And in particular, two things stir his compassion: our afflictions and – almost unbelievably – our sins.

Having experienced on earth the utmost load of pain, rejection and sorrow, ‘in all points tempted like as we are’ Christ in heaven empathises with our sufferings more fully than the most loving friend. And more: he has compassion on those who are ‘out of the way’ (that is, sinning; Hebrews 5:2). Indeed, says Goodwin,

‘your very sins move him to pity more than to anger… yea, his pity is increased the more towards you, even as the heart of a father is to a child that hath some loathsome disease… his hatred shall all fall, and that only upon the sin, to free you of it by its ruin and destruction, but his bowels shall be the more drawn out to you; and this as much when you lie under sin as under any other affliction. Therefore fear not, ‘What shall separate us from Christ’s love?’

The focus is upon Christ, but Goodwin was ardently Trinitarian and could not abide the thought of his readers imagining a compassionate Christ appeasing a heartless Father. No, he said, ‘Christ adds not one drop of love to God’s heart’.11 All Christ’s tenderness comes in fact from the Spirit, who stirs him with the very love of the Father. The heart of Christ in heaven is the express image of the heart of his Father.

How we need Goodwin and his message today! If we are to be drawn from jaded, anxious thoughts of God and a love of sin, we need such a knowledge of Christ. If preachers today could change like Goodwin to preach like Goodwin, who knows what might happen? Surely many more would then say as he said ‘Christ cannot love me better than he doth. I think I cannot love Christ better than I do’.

Michael Reeves

Oxford

August 2011